Targeted solutions for a world of hunger

Imagine that you are driving to your favorite campsite. You turn a corner and you hear a pop! You pull off the side of the road and check your tire. It’s a flat. You think to yourself I know how to change it, but when you get the wrench, it’s gone. You try everything to get someone’s attention. Finally, you see a cloud of dust approaching. When a man passing by stops, you explain your situation. The man grabs a crisp $100 bill. He throws it out the window and speeds away. Usually this generous gift would brighten anyone’s day, but it was the wrong gift at the wrong time.

The gift this man gave is like the food aid often given to third-world countries. Foreign food aid is not an uncommon practice. In fact, over the course of 9 years, the United States spent $17.9 billion on food aid. For comparison, if every dollar was one acre, it could cover the United States 7.7 times.

World hunger is best addressed by a multitude of people with a variety of skills that can be applied to location-specific problems.

Let’s discuss the pervasiveness of hunger, then address problems with some food aid strategies, and lastly, suggest long term, sustainable solutions.

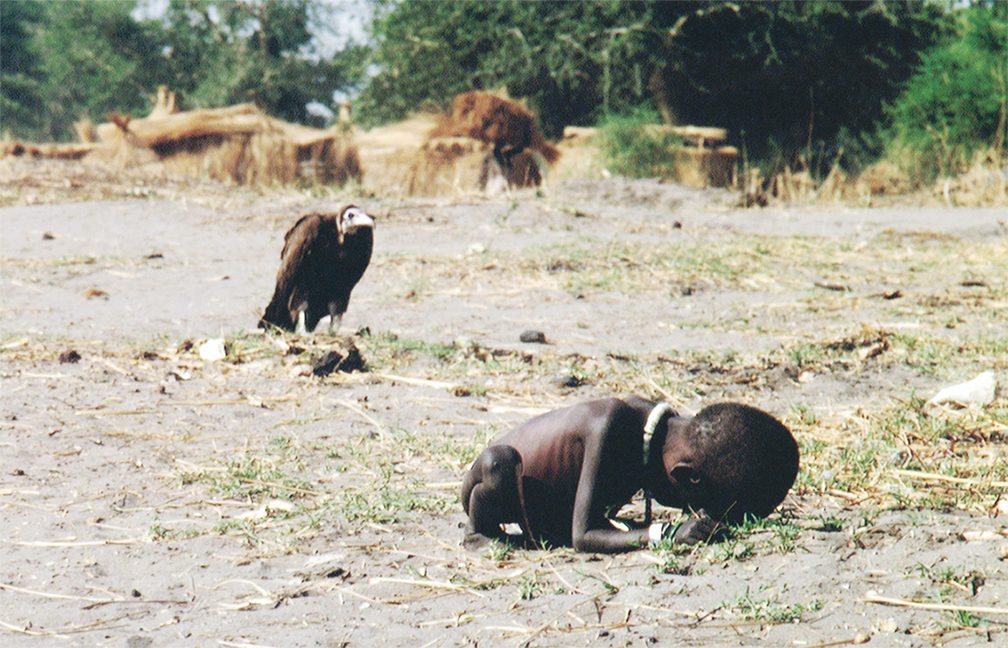

As Americans we are desensitized to the word hunger. How many times do you hear someone say, “I’m starving, and I could kill for a Big Mac,”? Let me explain to you what hunger is. In 1993 Kevin Carter, won the Pulitzer Prize for a photograph that depicts an emaciated girl, crawling from exhaustion towards the United Nations food center. Just 10 meters behind her, a vulture stalks, waiting for his next meal. A vulture named Hunger. I want you to forget the definition of hunger related to how you felt when you skipped breakfast, and instead focus on the hunger this little girl faced. Worldwide 795 million people are food insecure meaning they do not know where their next meal will come from.

Admirably, people in developed nations are not sitting idly by. The food center this girl hoped to reach fed 45 million people last year (Programme, 2017). Everyone has heard at least once, “For $5, you can save a starving child.” However, there is a problem with this kind of food aid. In his book, Howard G. Buffett explains the story of an Ethiopian woman named, Adanech Seifa. She has 1.25 acres land, that has not produced enough to feed her family in months. Food aid from the U.S will feed her family for a day or maybe a month, but when that food is gone, they’re back to the same problem as before. It is as the saying goes, “You give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. You teach that man to fish and you give him an occupation that will feed him for a lifetime.” (Lao Tzu, 601 B.C.E).

Current methods for solving world hunger are often short-term. There are many logistical and situational errors and inefficiencies in these gifts. I am proud to live in a world that has spent so much time and resources helping the less fortunate, still, there are some longer lasting solutions on which we need to focus.

Some solutions that would be even more effective are encouraging the implementation of extension agencies in developing nations or providing alternatives for those nations whose governments are not capable of administering extension agencies. Another solution is focusing on location-specific ideas that consider local cultures, soils, climates, and market supply routes.

One way we can help third-world countries is encourage it’s governments to fund and create extension agencies and therein, extension agents. These agents can answer questions a farmer may have and provide access to research. However, many governments unable to facilitate extension agencies. In cases such as these, food aid dollars already being spent, should be diverted, and spent enabling teams of extension agents to travel to countries in need.

When offering long-term solutions, localities and customs need to be considered. In Afghanistan and Iraq, warring factions are continually slashing and burning food crops. Dr. Ed Price works to help people in this region by teaching them to grow a crop called cassava. It grows underground and is not easily noticed by warlords. We need more winning ideas such as this. Food aid dollars can be better spent finding this kind of solution than on sending food because these solutions last longer.

Education and tools should also reflect the needs dictated by location. Americans typically encourage agriculture practices that work well in America. The best improvements in American agriculture are often related to advances in equipment. Too many times, aid is given in the form of new equipment and implements; while these are well meaning gifts, they often become useless.

If developed nations send extension agents to places in dire need, they could teach farmers to best cultivate their land. You see, without education, even the most generous gifts, are useless. If we do not educate the people before supplying billions of dollars of tools, those tools become dust collecting decorations.

If we re-evaluate our food aid measures, we can be more effective. Developed nations are pouring, often useless gifts into the hands of the hungry. By changing our strategies there will be fewer vultures and more fishing. Let’s stop throwing $100 bills and start changing tires. Let’s give the gift of educated, extensions agents, tools and ideas.

World hunger is best addressed by a multitude of people with a variety of skills that can be applied to location-specific problems.

Let’s discuss the pervasiveness of hunger, then address problems with some food aid strategies, and lastly, suggest long term, sustainable solutions.

As Americans we are desensitized to the word hunger. How many times do you hear someone say, “I’m starving, and I could kill for a Big Mac,”? Let me explain to you what hunger is. In 1993 Kevin Carter, won the Pulitzer Prize for a photograph that depicts an emaciated girl, crawling from exhaustion towards the United Nations food center. Just 10 meters behind her, a vulture stalks, waiting for his next meal. A vulture named Hunger. I want you to forget the definition of hunger related to how you felt when you skipped breakfast, and instead focus on the hunger this little girl faced. Worldwide 795 million people are food insecure meaning they do not know where their next meal will come from.

Admirably, people in developed nations are not sitting idly by. The food center this girl hoped to reach fed 45 million people last year (Programme, 2017). Everyone has heard at least once, “For $5, you can save a starving child.” However, there is a problem with this kind of food aid. In his book, Howard G. Buffett explains the story of an Ethiopian woman named, Adanech Seifa. She has 1.25 acres land, that has not produced enough to feed her family in months. Food aid from the U.S will feed her family for a day or maybe a month, but when that food is gone, they’re back to the same problem as before. It is as the saying goes, “You give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. You teach that man to fish and you give him an occupation that will feed him for a lifetime.” (Lao Tzu, 601 B.C.E).

Current methods for solving world hunger are often short-term. There are many logistical and situational errors and inefficiencies in these gifts. I am proud to live in a world that has spent so much time and resources helping the less fortunate, still, there are some longer lasting solutions on which we need to focus.

Some solutions that would be even more effective are encouraging the implementation of extension agencies in developing nations or providing alternatives for those nations whose governments are not capable of administering extension agencies. Another solution is focusing on location-specific ideas that consider local cultures, soils, climates, and market supply routes.

One way we can help third-world countries is encourage it’s governments to fund and create extension agencies and therein, extension agents. These agents can answer questions a farmer may have and provide access to research. However, many governments unable to facilitate extension agencies. In cases such as these, food aid dollars already being spent, should be diverted, and spent enabling teams of extension agents to travel to countries in need.

When offering long-term solutions, localities and customs need to be considered. In Afghanistan and Iraq, warring factions are continually slashing and burning food crops. Dr. Ed Price works to help people in this region by teaching them to grow a crop called cassava. It grows underground and is not easily noticed by warlords. We need more winning ideas such as this. Food aid dollars can be better spent finding this kind of solution than on sending food because these solutions last longer.

Education and tools should also reflect the needs dictated by location. Americans typically encourage agriculture practices that work well in America. The best improvements in American agriculture are often related to advances in equipment. Too many times, aid is given in the form of new equipment and implements; while these are well meaning gifts, they often become useless.

If developed nations send extension agents to places in dire need, they could teach farmers to best cultivate their land. You see, without education, even the most generous gifts, are useless. If we do not educate the people before supplying billions of dollars of tools, those tools become dust collecting decorations.

If we re-evaluate our food aid measures, we can be more effective. Developed nations are pouring, often useless gifts into the hands of the hungry. By changing our strategies there will be fewer vultures and more fishing. Let’s stop throwing $100 bills and start changing tires. Let’s give the gift of educated, extensions agents, tools and ideas.