Destruction and vandalism exhibit

The College of Eastern Utah’s Prehistoric Museum art gallery is hosting a fall semester exhibit created by instructor Pam Miller’s museum exhibition class that explains the importance of understanding how the destruction and vandalism done at paleontology and archeology sites impact the study of ancient peoples.

Protection of paleontology and archeology sites is covered under a 1906 act passed by congress called the Antiquities Act,” Miller said. “It’s not a new law. It’s almost 100 years old and it has virtually not changed.”

The College of Eastern Utah’s Prehistoric Museum art gallery is hosting a fall semester exhibit created by instructor Pam Miller’s museum exhibition class that explains the importance of understanding how the destruction and vandalism done at paleontology and archeology sites impact the study of ancient peoples.

Protection of paleontology and archeology sites is covered under a 1906 act passed by congress called the Antiquities Act,” Miller said. “It’s not a new law. It’s almost 100 years old and it has virtually not changed.”

Passed under President Theodore Roosevelt, the act was created for the preservation of American Antiquities on June 8, 1906. It essentially states that no person shall appropriate, excavate, injure, or destroy any historic or prehistoric ruin or monument, or any object of antiquity, situated on lands owned or controlled by the government of the United States.

Upon conviction, a person will be fined in a sum of not more than $500 or be imprisoned for a period of not more than 90 days, or shall suffer both fine and imprisonment, at the discretion of the court.

The law is important to understand, explained Miller, because it describes what people can and cannot do at historic sites. One can take photos, draw, plot on a map or GPS unit and record at a museum or local government agency.

If someone vandalizes a local site, then potentially 35,000 people a year who visit the local museum will not see the object which could help record a significant historical event or people, says Miller.

Another instance is when people pick up dinosaur bones. “The bone they take may be the one needed to help give a clue or diagnostic into what type of species it belonged to,”she said.

Miller’s class chose a topic fall semester to research, came up with a theme and established learning, behavior and emotional objectives. They created an exhibit-planning document and spent second semester designing Her personal favorite is an empty case with sand that was designed for the exhibit. The label read that the artifact that was found at the site was sold to another state or country and therefore could never be seen by visitors at the CEU Museum. The impact of the empty case tells a story more than a photo or exhibition, she said.

The exhibit is an educational one that lets the public know what they can and cannot do when they find historic sites. Scientific knowledge is forever lost when people vandalize and destroy what little remains of our past, Miller said.

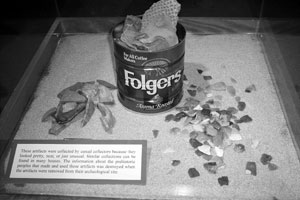

A beautiful pot, maybe 2,000 years old, sits in pieces in one of the museum cases. It’s caption reads, “These artifacts were collected by someone who thought they looked pretty, neat or just unusual. Similar collections can be found in many houses – the information about prehistory peoples that made and used these artifacts was destroyed when the artifacts were removed from their archeological sites. These pots were used as shotgun targets and destroyed.”

Besides the paleontology and archeology vandalism exhibition, the 16 years of posters from the state of Utah’s Prehistory Week are on display. “The one we are most proud of is the one the fourth grade class of Creekview Elementary designed in the late ’90s,” she said.

The museum is open Monday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. and is located on 100 north and 200 east in Price. The art exhibit is located on the mezzanine on the second floor.