Proteins are the Future of the Agricultural Business

If agriculturists are not able to gain control of the supply chain the future of agriculture will not flourish.

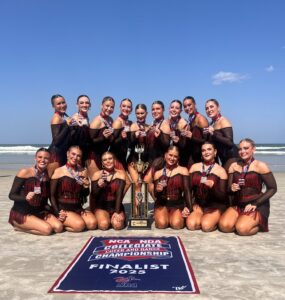

Picture by JJ Briseno

If agriculturists are not able to gain control of the supply chain the future of agriculture will not flourish. As it is, there is an incestuous relationship between agriculture and big businesses that thrives in the dark, and it’s time to shed some light on the industry, market, and future structures that can create by-product production and increase the control of local supply between grower and consumer.

Let’s dive into the logistics of popular proteins such as beef as well as less popular proteins such as goat and sheep. I have solicited the help of local producers of each protein in Carbon and Emery counties, and in other rural Utah areas. For the purpose of this article I will keep their names anonymous.

First, let’s discuss the differences between multi-generation farming, first-generation farmers, and multi-generation farming without the inheritance of capital in the form of land, animals, and implements. Inheritance always aids in the development of an operation’s size and markets to scale.

When a child of a farmer inherits land, livestock, permits, and equipment, the money they would have spent on the initial investments can go to new markets, and much more. The business will grow and more easily enter other industries.

Beef:

The consumer’s inconvenience is the beef growers’ largest barriers for gaining more control of local markets. Few people have the freezer space for a full beef, or the money to spend up front for a steer on the hoof or hanging. They instead pay for beef as they need it at higher prices for lower quality.

One option local growers have to gain more control of the market is to create a farmer-owned co-op that buys from locals and has an in-house butcher where the meat can be inspected, cut and wrapped ready to be sold at market price. Unfortunately, producers, be it beef, corn, or wool, are price takers and never price makers. Consumers set the price for all except the largest producers. Waiting to sell for a future price means spending money storing or feeding for an additional year, or selling at auctions. There are downsides of auctions in all industries. For example, animals must be trailered in.

There are ways for producers to control the supply chain in various ways. They include niche marketing, agritourism, strategic by-product sales, and vertically integrated marketing. Finding niche markets lets farmers become price makers for specific products. This gives them a small window in every category of production.

Agritourism can be dude ranches, corn mazes, pumpkin patches, and orchards. A first generation or recently started business will be at a disadvantage to agritourism structures passed down and marketed for generations.

Other opportunities include cross country horse races with vendors, camping, parking, and fires, as well as horse-drawn rides, farmers markets, and ATV rides.

A large by-product market in the beef industry is leather. However, there are 111 leather tanning facilities in the United States and more and more specialize in wild game hides instead of cow hides. If beef growers could break in, tanned cowhides could be sold as rugs, and tooling leather could be sold to private individuals as well as businesses. This market is most likely to be obtained from butchers, feedlots, and vertically integrated business models.

One of the most common vertically integrated beef markets is jerky that can be marketed as artisan, fresh, or homemade and bring higher prices than brand-name jerky in convenience stores.

Sheep:

Sheep is a lesser protein but its demand has risen steadily with the influx of immigrants into the area. Sheep has the same benefits as beef, plus the by-product sales of wool. Now, most wool growers have been selling raw wool right off the sheep. But one of the largest wool buyers in the country is the U.S. Army which acquires nearly 25% of wool produced. However, they only buy as needed, not in surplus, and wool producers have been known to sit on sheared wool for years.

There is a brighter future for wool because it can be spun locally and spun into a usable thread, which can be made into blankets, crocheting yarn, bows, and more.

This provides a local good that is otherwise hard to find. The by-products of sheep can increase profits above meat production and in businesses where prices can be set.

Goats:

Much like beef and sheep, goats would benefit from farmer-owned cooperatives, but they encounter the hardship of being a less-popular protein and victim of market slaughter.

Goat producers have been forced to take market prices or make nearly unattainable contracts with feedlots that are not easily met. Goats milk could benefit from niche marketing and strategic advertisement. It’s most commonly used for supplements in weaner calves, or a protein substitute in young pigs. Goats milk could also be used for those individuals with sensitivities to dairy in cooking ingredients, drinks, and butters.

An unusual use of goats is in the energy fields. No, they’re not used for mining coal or turning wheels, but to eat down vegetation along power line plots, and as fire management. When the job is done, they are sent off for meat production.

The future of agriculture and the producers’ livelihood is dependent on gaining control of the local supply chain. It will take work from local and state agencies working towards the same goal. It will require producers to work with their competitors, develop skills outside of the normal, and think outside of traditional production.