Utah biologists track black bears to monitor population growth

Playing hide-and-seek with friends is an exciting game of chase and a little bit of sneakiness.

Now imagine playing hide-and-seek not with friends, but with a hibernating black bear weighing more than 300 pounds, with cubs in her care. Brad Crompton, a biologist with the Department of Wildlife Resources, and other biologists go into the wild several times each year seeking for these hiding bears.

Several times each year, biologists seek out radio-monitored bears in the wild to collect population information.

This archived article was written by: Kurt Hanson

Playing hide-and-seek with friends is an exciting game of chase and a little bit of sneakiness.

Now imagine playing hide-and-seek not with friends, but with a hibernating black bear weighing more than 300 pounds, with cubs in her care. Brad Crompton, a biologist with the Department of Wildlife Resources, and other biologists go into the wild several times each year seeking for these hiding bears.

Several times each year, biologists seek out radio-monitored bears in the wild to collect population information.

More than five years ago, the DWR began placing radio collars on black bears to monitor population growth. Several times each year, biologists traverse the wild, looking for 13 of these bears to check on health, size and breeding. Using the information they gather, they can view trends in population growth. On March 3, Crompton, a team of biologists and students from the College of Eastern Utah searched outside of Price for one.

They started out from a dusty road on a cold Utah morning. The journey was going to be rugged, but more rugged than anyone expected. There was no trail and no one knew where the bear was hibernating. All Crompton knew was a plane arrayed with tracking equipment flew over earlier in the week and picked up the collar’s frequency in the cliffs.

“Our point is to teach the students that once humans have an impact on their environment,” Krum said, “they have a need to manage their environment.”

The terrain was demanding. The team members climbed steep embankments of snow and traversed escarpments of loose gravel like billy goats. An ETV reporter from Price even carried his camera and tripod with him the entire way, more than 10 miles. All for the hopes of finding a bear.

“The bears live in some fairly remote country,” Crompton said. “Most of the bears we go to require a snowmobile ride and snowshoes.”

Eleven a.m. was nearing and the team found a spot to rest while Crompton unsheathed his telemeter. A telemeter is an instrument used to detect proximity to a target, or in this case, the bear. The closer the target, the louder the telemeter beeps. Crompton held the instrument high in the air and slowly rotated it. And then, he heard a beep. A loud beep. He pointed the object where he presumed the signal was coming from. The beeps sounded louder.

The team pressed on and the terrain became more difficult. But Crompton and his team were not afraid. Brent Stettler, conservation outreach manager at DWR was grateful for the terrain. It could have been worse. It could have been a canyon. Stettler said canyons reflect the radio signal and make it extremely difficult to find the exact signal.

“It can be kind of a guessing game,” Stettler said.

On the team was Jon Krum, a biology professor from CEU, and a group of his students. His students were given the option to view the bears as an alternative to writing a paper for the class.

“My role is to provide them with opportunities to do something that they may never have a chance to do again,” Krum said.

Around noon, Crompton told the team to quiet down. They were nearing the den and he did not want anyone carelessly waking the bear. The whole trip would be a waste were that to happen.

And then, he found her. What they had all been waiting for. Armed with a syringe, Crompton scurried into the sleeping bear’s cave and shot the bear with tranquilizer. Down she went. Black bears are lethargic when woken from hibernation, so tranquilizing was not a problem.

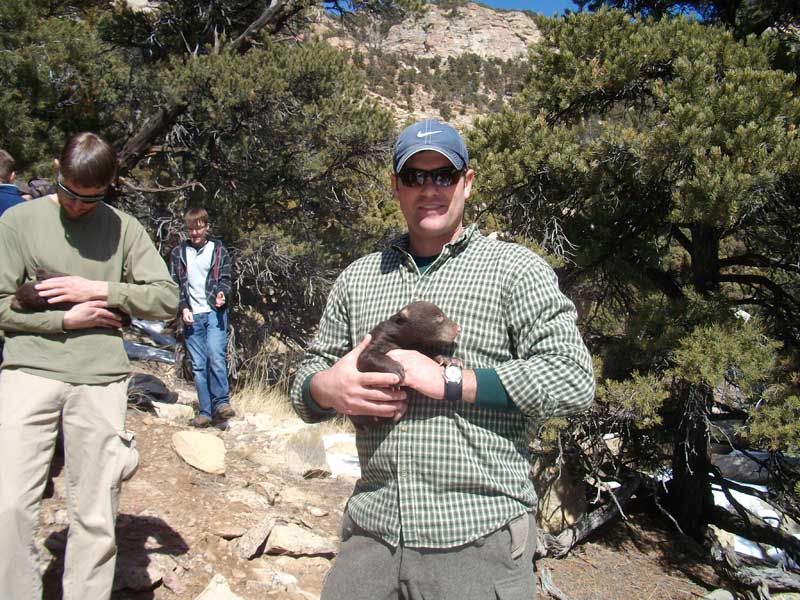

Crompton inspected the bear and applied antibiotic to a wound developing from the radio collar. He then carried her two cubs out for the team to see and hold. They were small, probably five pounds. No larger than a large puppy, but certainly more feisty. Claws had developed and they were growling. They wanted to go back to their momma.

After Crompton inspected the health of the cubs and the sow, the team said good-bye to the little balls of fluff and the bigger ball of fluff and started the return journey. The next year, Crompton will return to the bear and her cubs to continue to monitor her health.

Krum said it’s good that people are making a positive impact on the environment. Crompton and other biologists make a constant effort to ensure safety for these bears.

“Our point is to teach the students that once humans have an impact on their environment,” Krum said, “they have a need to manage their environment.”